31: U.S. Power and Reputation After COVID-19

Another edition of Aha! - soft power and why it's important

Hello, friends,

After writing three or so newsletters about COVID-19, a few of my friends were anticipating that I would keep them up; that Catalog of Curiosities would, for the time being, become a COVID newsletter. I found the idea intriguing, yet the more I thought about it, and the more I read up on it, I found that task to be one, too time-consuming considering my other commitments; and, two, the more I read on it, the less I felt confident in reporting anything on it. I made a good choice.

That said, I did start drafting one a few months back called “How to think About COVID-19?” that will probably never see the light of day. The very last newsletter I did publish about COVID-19 said that if I would write more on it, I would look at solutions. I still think that newsletter—where I summarized Sahm’s basic idea of strengthening automatic fiscal stabilizers—holds up: when economic recessions begin, automatic fiscal stimulus kicks in (for whatever amount) until the economy is out of a recession. Yeah, we should get on this.

And obviously we should begin building into our infrastructure, trade agreements, public health agreements, fiscal and monetary policies, and so forth, resiliency measures that prioritize public health, nominal GDP-growth, rent support, and so forth. The tools we have at our disposal are actually enough; it’s the political will that isn’t there. I also support fully funding an international global vaccine organization, that prioritizes universal delivery (this, for COVID, is known as the Access to Covid-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator) as opposed to what we are seeing now: U.S. funding it’s own program (Operation Warp Speed). Other countries are also engaging in “vaccine nationalism.” Global cooperation is the only ethical path forward - U.S. leadership could have really made this more likely to be successful. Instead, Trump has suspended funding to the World Health Organization (WHO) and announced the U.S. would not join COVAX, the WHO-led effort that would facilitate the ACT Accelerator.

In the end, the 21st-century needs to be governed with 21st-century institutions, not 19th-century ones. But this requires responsibile leaders who have a sophisticated, and cosmopolitan understanding and normative commitments that the interconnected 21st century global economy demands. In this age of climate change, global supply chains, arms-proliferation, a growing global middle class, and an aging demographic with a popluation growth trend now reversing from expectations, little decisions become huge; huge decisions reverberate spatially and temporally; and managing the lives of nine billion people who can increasingly reach one another becomes utterly a monumental task.

And, of course, other U.S.-focused solutions from experts have been put out and largely ignored because of our 50-state free-for-all Royal Rumble ad-hoc non-plan plans approach. If we can’t have responsible governance at home, we can’t deliver responsible governance abroad. This brings me to the latest edition of Aha!

~

One of my closest friends asked me a question that I really found thought-provoking and precisely aligned with a couple of projects that I’m working on. One of them is preparing to teach U.S. foreign policy in Spring 2021; the second being my dissertation, in which I am theoretically exploring Barack Obama’s foreign policy across several cases. The question my friend asked was:

You say COVID-19 will be endemic. I don't disagree with you. But, what is that going to mean for the US position internationally in the coming decades? Other countries are not going to accept COVID-19 as endemic if they are able to avoid it. It's not going to be the cost of doing business with the US, or of having us in their borders.

Next, I prologue my answer and then in my column Aha! I explore the concept of “soft power” and power in general to elucidate my answer.

My friend’s first sentence refers to the claim that COVID-19 will become an endemic virus and disease, one that stays with us permanently. This is obviously the outcome for most viral diseases: malaria, tuberculosis, AIDS, and rubella syndrome. Rubella has been effectively wiped out in the U.S. due to vaccines; around the world, however, upwards of 100,000 babies are born each year with congenital rubella syndrome (Osterholm and Olshaker 2017, 65%) And, more importantly, we already have four endemic coronaviruses. So, yes, as James Hamblin writes, “cold and flu” season will become “cold, flu, and COVID-19 season.” Therefore, I disagree with my friend that “other countries are not going to accept COVID as endemic.” They are going to have to; and blame, in the end, only matters regarding hard-to-measure metrics such as prestige and reputation. Every nation-state is going to do what they need to do, materially speaking, to keep up with the science, the supplies, the institutions, and so forth, needed to meet public health challenges, including COVID-19.

Besides, U.S. prestige and reputation have not looked good for a while; and this is not the first administration to be viewed as a unilateral bully.

“NATO gets short shrift, the United Nations is an afterthought, treaties are not considered binding, and the administration brazenly sponsors protectionist measures at home such as new steel tariffs and farm subsidies. Any compromise of Washington’s freedom to act is treated as a hostile act” (Hirsh 2002).

No, this passage is not from 2017-2020 or about Donald Trump but from 2002 and about George W. Bush, who was only a year into what turned into a two-term presidency. By the end, he only had 11% of Americans believe he did an above average job. This was “the lowest positive end-of-term rating for any of the past four presidents” (Pew 2008). Bush was considered belligerent, uncivilized, and ignorant of the history of Europe, US-led multilateral efforts, and so forth. This brings me to another edition of Aha!

Aha! - Soft Power

Aha! is a column which I discuss terms that illuminate the way through~

A few years after the aforementioned Hirsh article, Joseph S. Nye Jr, who coined the term “soft power,” referring to the ability to “get others to want the outcomes that you want (Nye 2004a, 7%),” reported on global opinion polls from 2004 that showed declining trust in the U.S.

“Anti-Americanism has increased in recent years, and the United States' soft power -- its ability to attract others by the legitimacy of U.S. policies and the values that underlie them -- is in decline as a result. According to Gallup International polls, pluralities in 29 countries say that Washington's policies have had a negative effect on their view of the United States. A Eurobarometer poll found that a majority of Europeans believes that Washington has hindered efforts to fight global poverty, protect the environment, and maintain peace. Such attitudes undercut soft power, reducing the ability of the United States to achieve its goals without resorting to coercion or payment” (Nye 2004b).

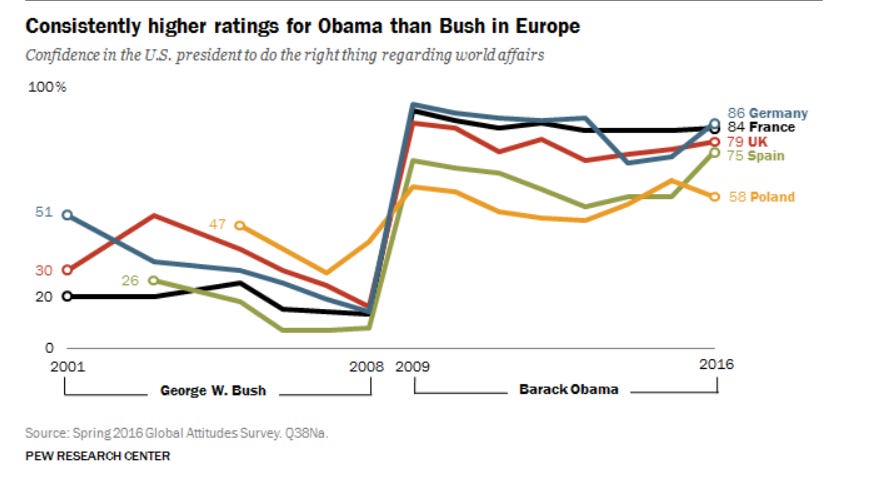

American reputation and prestige increased during the Obama years:

As Buttigieg and Gordon note below, when asked if they had confidence the U.S. president would “do the right thing,” during the Trump years, global public opinion has turned sour, once again, on the leader of the U.S.

“The collapse in global regard for the United States has been breathtakingly swift under this president. Even before collapsing further due to Trump’s mishandling of the pandemic, confidence in him to ‘do the right thing’ in international affairs stood at just 29 percent among 32 countries polled—down from 74 percent in former President Barack Obama’s final year in office. Global confidence in Trump is significantly lower than in German Chancellor Angela Merkel (46 percent), French President Emmanuel Macron (41 percent), and Russian President Vladimir Putin (33 percent)—and just one point higher than in Chinese leader Xi Jinping (28 percent). Germans are now equally divided on whether the United States (37 percent) or China (36 percent) is their closest partner, while just 28 percent of Britons trust the United States to act responsibly. Confidence in Trump is only 36 percent in Japan, 32 percent in the United Kingdom, 28 percent in Canada, 28 percent in Brazil, 20 percent in France, 13 percent in Germany, and a mere 8 percent in Mexico, while favorable views of the United States have fallen from 64 percent in 2016 to 53 percent in 2019. Asked in June whether she trusted Trump, Merkel paused before saying only ‘I work with elected presidents around the world, including, of course, the American one’.” (Buttigieg and Gordon 2020).

Now I get to my answer regarding how will the failure of U.S. leadership impact how the world sees the U.S.

I think COVID-19 won’t change much as far as the continued decline of the U.S. is concerned. I agree with Stephen Walt, Richard Haass, and Kori Schake that nation-states will become more nationalistic, xenophobic, and focused on domestic politics for quite a while; and that the U.S. “has failed the leadership test,” as Schake (2020) puts it. COVID-19 will accelerate already existing dynamics as opposed to ushering in a hairpin turn of developments. What are the existing dynamics? Per Haass: “increased great-power rivalry, nuclear proliferation, weak states, surging refugee flows, and growing nationalism, along with a reduced U.S. role in the world.” The title and subtitle of the Haass article capture my opinion: “The Pandemic Will Accelerate History Rather Than Reshape It: Not Every Crisis Is a Turning Point.”

I largely think that the big macrotrends and well-treaded paths, both domestic and internationally, that were coming into focus before COVID-19 will continue to head in the status quo ante direction. Here are three reasons, both domestic and international, why the continued decline of the U.S. is likely to occur.

(1) Domestic American politics is broken.

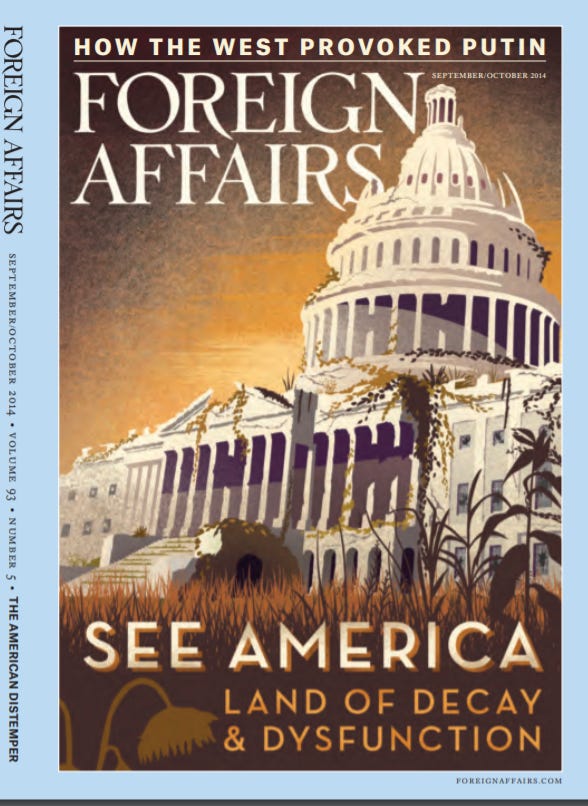

In an era of polarization, which counter-intuitively produces closer elections and what political scientist Frances E. Lee calls “insecure majorities” incentivizing vetoing and blocking, because it’s always just two years until you have a chance to take back one body of government in the U.S., the maintenance and reform needed will not likely happen. On top of polarization, recent work by two esteemed political scientists argues that “American democracy has never faced so many threats at once.” They list four threats, including polarization, that demand that “in evaluating a policy or proposal, Americans should lean away from their ideological tendencies, material interests, and partisan preferences and instead focus on whether the measure at hand will reinforce democracy or weaken it” (Mettler and Lieberman 2020, 195). When one of these threats—polarization, growing income and wealth inequality, excessive executive branch authority racial unrest—exist inside a democracy, it can begin to decay. When all four are present, you are in serious trouble. A 2014 cover of Foreign Affairs captured this situation starkly:

This above call for prioritization of democracy over anything else will not happen; particularly because of polarization and because party politics is about power, more so than any notion of “democracy,” or “liberalism,” or “patriotism.” And when one party is committed to being an insurgent, anti-democratic, anti-majoritarian, anti-civilization force, in a two-party duopoly, expect more chaos, not less. And when the other main party is prone to infighting, bikering, and beholden to its donor class, the country’s needs are left to fester. To be blunt, American politics is broken and it was broken by political and economoic actors prioritizing rent-seeking over actual pluralism, which is the sinew of liberal democracies.

(2) U.S. power, soft and hard, is not what is used to be

Soft power is a fragile thing, just like personal reputations are. If you lose respect for someone, it’s hard to gain it back, even if you want to. The psychology there is fascinating. The same holds true for governments. If Trump wins again, this decline is even more guaranteed to be steep. Even if Biden wins, anticipate Europe becoming less trustworthy of U.S. commitments still. The old order is not coming back, and this was even admitted to by former President Obama’s deputy national security advisor Ben Rhodes in a recent essay. Power in IR is conceptualzied as the ability to translate raw power into results, achievements, prestige, trust, respect and emulation. It will take work for the U.S. to rehabilitate its image. But it’s also going to be increasingly hard to do so even if we managed to do so perfectly because of the “rise of the rest,” the China challenge, and globalized and diffuse power. This brings me to my final reason of a continued decline of U.S. prestige and influence.

(3) Power, in general, is not what it used to be — its diffuse, scattered, up-for-grabs An order based on what I am calling “disruptive multipolarity” will continue to accrete and form. This disordering of the world, one that resembles the 19th-century “balance of power” and “realpolitik” more than the post-war liberal international order, will only accelerate after the failures of COVID-19. And it is intimately tied with the previous reason; American soft power is shot. Sure, it’s possible that a vaccine champion will emerge, but what is more likely to happen is “vaccine nationalism,” increasing resentment. In fact, contrary to my expectations, of a world of multiple powers building networks or blocs in an attempt to solve global collective action problems, we might be in a G-Zero world, defined by Ian Bremmer as a “world order in which no single country or no enduring alliance of countries can meet the challenges of global leadership (2012, 3%). But that development would still be somewhat congruent with the order that I anticipate: an order that is “nasty, short, brutish.” The world order might not be multipolar, it could be apolar; what it is for sure is in disarray, being disrupted, and has not yet reached an equilibrium of any sort.

So, ultimately, I think U.S. leadership and the outcomes in the U.S. regarding COVID-19 signify, illustrate, and are symptoms of the already existing power dynamics and power distribution that is emerging; and also of the rotting decay of American political institutions. This is not to say that another president can’t rehabilitate America’s prestige and reputation. I believe positive change can happen. Not all is lost. However, I say:

Welcome to the Age of Disruption,

Patrick M. Foran